Neighborhood:

Lakeshore/Lake VistaBar: Pontchartrain Point Cafe

Drink: Abita Amber (Draft)

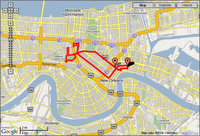

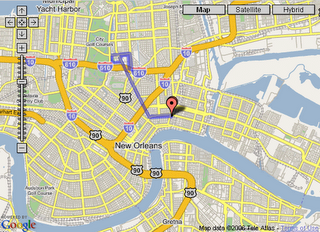

From river to lake, New Orleans must be around eight or nine miles. Following Orleans Ave. all the way from Tremé, the terrain changes so completely that it feels much farther: setting out at the empty and vast Lafitte housing project--metal plates covering the doors and windows, No Trespassing signs on every unit--you wind your way up through haggard and half-empty Mid-City, out past Bayou St. John (more drainage canal than bayou), up through the tranquility of City Park, where kids play soccer again and the green has returned, continuing on up to the very top of the park, past the riding stables where I saw an Appaloosa placidly cropping new grass, and finally arriving at the park-studded cul de sacs of Lake Vista, nestled between park and lake shore.

Lake Vista is the closest New Orleans comes to suburban idyll. If not for the great Live Oaks that shade the communal parks, this neighborhood could be anywhere. Well, anywhere affluent. The residents had posted hand-lettered street signs to replace those that disappeared in the storm. A particularly lovely one graced the corner of Warbler and Swallow: a trompe l'oeil pattern imitating decorative ceramic tile, complete with images of the eponymous songbirds.

The pattern of damage here is almost impossible to trace: seemingly untouched houses stand next to gutted shells or houses with no visible damage except the tell-tale FEMA trailer. A resident I asked explained that the water from the 17th St. Canal breach flowed out toward the city before settling back in these areas when the water levelled. Still, it's puzzling to see houses just yards from the lake utterly untouched by the flooding.

Speaking of the lake, last Wednesday the view there was ridiculously beautiful. Sailboats bobbing on placid water before a sherbet-colored sunset. It reminded me of one of those inspirational workplace

posters: "Dreams: Believe in your own; crush those of your underlings." Or something like that.

From the lakeshore, I doubled back to my intersection of the week, Gen. Haig and Jewel, which just happened to be the site of one of the few levee system

upgrades that the Corps of Engineers finished on time. It was here that I saw perhaps the surest sign that things are changing. So, I took a photo of it:

You can imagine my relief.

I pulled up to one of the canal levee walls and leaned my bike against a tree, studiously ignoring the security patrol car that slowed and hovered near my bike. At the top of the levee, I surveyed the scene. The Orleans Ave. Canal did not breach (although, apparently it did overtop nearer Midcity). Each side of the canal itself is bordered by boulders and stones not native to this part of the country. Giant stands of bullrushes spring up in a bend upstream. Mullets jump purposelessly. Across the way, a man fishes, pulling a long lure across the canal's surface. Above him, a massive construction crane is frozen in the act of lowering a large curved pipe, like something on the deck of a cruise ship. Cicadas sing.

I left the tranquility of Lakeshore and decided to find a beverage. Around West End, the Lakeshore takes on the air of an oceanfront town, and here you could once find rows of seafood restaurants just across from the yacht club. It was getting dark as I passed Joe's Crab Shack, but still I could tell it wasn't coming back anytime soon. Sail boats still appeared tossed about in the docks. Many were under repair, some back under sail, others looked abandoned.

At first I thought the restaurant row was completely deserted, but then I saw a sign announcing one place "Opening Soon," and down a side street I saw the parking lot of the Pontchartrain Point Cafe full of cars.

Inside, I ordered a half-pint and eavesdropped on lawyers talking cases and politics. The customers not wearing suits wore polo shirts with yacht-club insignia. Employees or members? Not sure. Beside me at the bar, two middle aged guys who hadn't seen each other since the storm went through the standard litany: for one, no flooding but a new roof, mother-in-law's Biloxi house completely washed away, so he had bought her a house nearby, tree recently removed; the other's place? he shook his head, named the neighborhood; that was enough. His boats? Lost one of the three; not complaining.

Alex, our bartender, knew everyone's name, including mine after my first drink. She turned to one of the guys at my elbow: "Mike, how you doing?"

"Crazy as a shithouse rat."

"Well, I knew that. Scotch?"

"Yeah, and a menu. I always order the same thing, but it still takes me an hour to decide. Go figure."

I struck up a conversation with Mike in the usual way we have now, "How'd you do in the storm?" Surprisingly easy to get into it. He said his was one of three houses on the block that didn't flood. His house is 7 feet above grade; his nextdoor neighbor at 6' 8" had flooded.

"Felt guitly as hell about it for three months. Depressed. Everybody's telling me I'm crazy, which I guess I am."

I asked him if people were coming back to the neighborhood. "Here, yes. In Lakeview, no."

We talked about his mother-in-law's place, the relative merits of Lafayette, Baton Rouge, and Alexandria as places to evacuate. "Baton Rouge has no culture. There's maybe one, two decent restaurants in the entire place. Well, before. Now they got Galatoires, all the rest."

A friend of his stopped by and chided him: "I thought you'd quit drinking."

"I did. I go back and forth, you know."

"Well, I'm just gonna make sure you only have one. You need to take it easy, now."

Later on we started discussing the bad habits we'd readopted in the past year. He told me he used to be in AA, and there was one guy in his group who was the pillar of AA, the member everyone else relied on. After the storm, he sees the guy in a liquor store, carrying a case of beer and a bottle of Dewars. "I ask him, 'How you been doin?' 'Not so good,' he says."

I took the long way home, looping around the other side of City Park. I crossed the I-10 overpass in near-total darkness. To my left, the L.S.U. dental school building looked like a deserted prison. (Of course, in the best of times it looked like a working prison, so there you are.) I could see the lights of the CBD off in the distance, but not much light between here and there.

Riding my bike around the lake front reminded me of the Abitaman triathlon I'd seen up there the summer before the storm. I was in training for a triathlon myself (and no, I'm not kidding), although since I'd only been training for four months, I didn't think I was quite ready yet. At the very back of the pack was a competitor who must've weighed nearly 300 pounds. As he came out of the water, I wondered, first, how he could possibly finish the race, and second, if he could do it, why couldn't I? I watched the leaders finish the bike portion, and met up with Sarah for a long walk along the lakeshore. As we headed back to the car, we saw the race crew folding up the water station tables, picking up the orange cones that marked the route and throwing them into a moving van. A few minutes after they passed, along came the big guy, completely forgotten by the event staff, not even part of the race anymore, but not giving up, either. He lumbered along, in obvious pain, and he still had another mile left. We applauded him as he passed, but I don't think he noticed.

So, as I stood on the I-10 overpass and looked back toward the city, I thought about that guy, and I thought about New Orleans. Sure, we weren't in the best shape before this all began. And, yes, it's true that everyone else will probably move on, and we'll be forgotten, chugging along far behind pace, receding into irrelevance. But remembering that big guy somehow made me feel a little better anyway.

Near the end of my ride, down on Esplanade, I heard the unmistakeable strains of a dixieland band, the clarinet carrying high out into the street. St. Anne's Episcopal Church had started a weekly supper and concert series to support New Orleans musicians, and this week's band was just wrapping up its set. I leaned my bike against a pole and watched them joke and laugh as they put their instruments away. And I thought to myself, "Go 'head on, fat boy."