Where I Got Them Shoes: St. Bernard Area Edition

Neighborhood: St. Bernard Area

Neighborhood: St. Bernard AreaBar: B&L Lounge (not in the St. Bernard Area)

Drink: Gin Tonic, High Life

Empty, empty, empty. That word kept circling through my head as I rode around the neighborhood of the St. Bernard project. One house after another, gutted, abandoned, silent now as they were a year ago. Front doors standing ajar reveal the bones of houses, two-by-four skeletons of dark rooms that left me feeling like a spectator at an autopsy, something simultaneously compromising and clinical. On streets whose names conjur luxury and glamour--Cadillac, Paris--there is instead an oppressive and pervasive torpidity, the weight of destitution.

Where the Lafitte complex seemed fortified against reentry, the St. Bernard project seems forgotten. True, it is shuttered as well, and metal plates do cover some of the windows and doors, but far more doors and windows are left wide open, and children's riding toys, bicycles, barbecue pits stand where they were one year ago. Inevitably, Pompeii comes to mind.

Back in June, protestors demonstrating for the right of return had set up a "Survivor's Village" on the neutral ground across from the main entrance to the housing complex. The tents they had pitched are now abandoned, the signs and banners left to the weather. Across from the tents and banners, behind the hurricane fence, weeds grow up around the sign marking the St. Bernard complex. Looking at the shells of apartments in this shell of a neighborhood, it's hard to imagine anyone ever returning here, hard to imagine wanting to return. But the call of home has its own ineluctable pull. That much I do understand.

A fair scattering of FEMA trailers mark the houses in the surrounding blocks where some have already returned. Functioning cars are interspersed among the abandoned wrecks, parked outside houses and apartments whose second storeys were undamaged. I heard a hammer here and there. One older gentleman was burning trash in his backyard, a sight quite common where I grew up, but, as you might imagine, not so common in urban New Orleans. He smiled and waved, seeming eager to strike up a conversation. I waved but kept pedaling, reluctant, for some reason, to stop.

On the fields behind the deserted Edward Henry Philips Jr. High School, the football team from McDonough #35 was wrapping up practice. I was drawn to the sound of kids' voices, bantering, clowning, as they loaded the buses for home. I watched them for a while but, beyond asking the team's name, I still didn't much feel like talking. Broken windows marked the face of the jr. high school, and weeds nearly covered the nursing home across the street.

I passed a couple of small groups of neighbors and family members who carried on the tradition of stoop-sitting in the only way they could now. One group had set lawn chairs outside the 7-foot hurricane fence behind the housing project, where they chatted over an Igloo ice chest full of bottled Miller's. Another group gathered around a picnic table under the I-610 overpass. A lone old-timer sat on a lawn chair in front of his FEMA trailer. He seemed excited and surprised to see me, smiling and waving as though to a fellow castaway just spotted on a neighboring island.

As I pedaled past, my reluctance to stop and chat with these people weighed more and more heavily on my mind. I knew that, in part, it was related to my sense of survivor's guilt. But this was more than the self-consciousness of the disaster tourist. It was also a nearly subliminal awareness of the racial barriers separating me from the people who lived in the St. Bernard development. Before the storm, to bike around the project, around its immediate neighborhood even, would have been unthinkable. And even now, I couldn't get past feeling that I was an alien here. I had internalized those barriers, and even the welcoming faces of the few returning neighbors couldn't convince me on the deepest level that those rules no longer applied.

On my way back downtown, I came across one of the few hopeful signs I encountered: Stop Jockin Barber & Beauty Salon, which had expanded its business to include a snowball shop, had evidently reopened since the storm. A snowball is the New Orleans version of a snowcone: a flavored ball of shaved ice. I had my mouth set for some creamy flavor--maybe a peach cream (drenched in condensed milk, of course), but apparently they had decided to close up shop a little early.

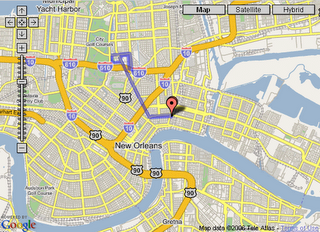

I still had fifteen minutes, according to the sign, but no one was around. Two FEMA trailers, where I imagine the proprietors are living, were set up in the side lot on what used to be a basketball court. I took a photo and headed back down St. Bernard Ave. toward the Marigny, passing the first (and only) "Re-elect Congressman Jefferson" sign I've seen.

I still had fifteen minutes, according to the sign, but no one was around. Two FEMA trailers, where I imagine the proprietors are living, were set up in the side lot on what used to be a basketball court. I took a photo and headed back down St. Bernard Ave. toward the Marigny, passing the first (and only) "Re-elect Congressman Jefferson" sign I've seen.Since there were no bars open in the neighborhood, I decided to have my official drink back downtown, and I knew immediately where I would have it: the B&L Lounge on Rampart St. It's the one bar in my neighborhood that I had never visited, and I had never visited it because I knew I would probably be the only white guy in the place. Many times I had walked by and smelled fish frying or crawfish boiling; I heard great blues from the jukebox through the open door. I recognized some of the people milling around the crawfish pot as my neighbors. Why should the simple act of having a beer with them be so damned fraught? (Well, besides the whole 300 some-odd years of past history, of course.)

Racial relations in New Orleans are impossible to understand from outside. And they're nearly impossible to understand from the inside, as well. I have never lived in a place more integrated than New Orleans. Black and white people know each other here in a way that is rare elsewhere in the country. But at the same time, in ways as subtle as the tilt of a head in greeting or as flagrant as the bigotry of the old Carnival krewes, New Orleans retains deep lines of racial segregation. Add to this the complexities of Creole identity, and suddenly you're faced with an intricate system of relationships, secret signs and subtle understandings that no one born elsewhere can really understand and no one born here can adequately explain. So, in the end, I decided, "To hell with it. I'm not going to understand it today, I'm probably not going to understand it tomorrow, and I'm certainly not going to change it. I'm going for a drink." And I did.

The B&L is pretty much exactly what you want your local to be: great jukebox (Aretha, Irma, Sam Cooke), cheap drinks, pool table. I had a gin-tonic and divided my time between watching the muted disaster movie on television and watching the bartender flirt with a patron. I was one of six customers at the time (two of whom never looked up from the video poker machines while I was there). I had a hot link (approaching, but not crossing, the line between spice-pleasure and spice-pain) washed down with a High-Life. It reminded me of nothing more than bars where old Cajuns hang out near my parents' place, bars in which old R&B is as likely on the jukebox as country songs or cajun two-steps, and in the afternoons and early evenings drinkers sit for long spells and listen to the music from their younger days and let their thoughts drift back. Like those bars, the B&L has its livelier side as well, event nights that bring the crowd and the rowdiness that force the afternoon drinkers from their reverie. By the time I left, the bartender had invited me back for the Thursday night fish-fry and the Monday night red beans and rice (a New Orleans tradition). There are squares open for the football pool, too, I hear. So, when the media frenzy descends for the reopening of the Dome, I think I'll stick to the neighborhood, wander back to the B&L and try out the red beans.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home