Neighborhood: LakewoodBar:

Neighborhood: LakewoodBar: Semolina

Drink: Pinot Noir, Sangria, Piña Colada (blame Lainie)

The Lakewood neighborhood isn't actually near the lake. It also isn't very woody. And, from what I can tell, it isn't really a neighborhood. Apparently, it's one of the many "official" neighborhood names that would make no sense to someone who actually lives in that neighborhood. The people I talked to in this odd uneven paralellogram of earth called their neighborhood Mid-City, a name which, in itself, might be confusing

to someone from, say, New York, where Midtown finds itself in the unsurprising space that separates Uptown and Downtown. But to look for Mid-City New Orleans between Downtown and Uptown would be like looking for Madison Square Garden in Madison Square. Mid-City is midway between the river and the lake, lying in casual disregard of the Uptown-Downtown relationship that orients the river-dwellers.

But whoever created the 73 divisions used in the GNOCDC map seems to have approached his or her task with a sense of near-Adamic license, and Lakewood seems to be the rhinoceros of New Orleans neighborhoods, strangely named and oddly shaped. Its sidelines are the 17th St. Canal (border with Jefferson Parish) and the I-10/Pontchartrain Expressway (originally the New Basin Canal). The dominant features are massive cemeteries and the New Orleans Country Club. In addition, the neighborhood is further subdivided by railroad lines and a curve of the interstate. All of which, I'm hoping, excuses the rather embarassing fact that I was effectively lost during much of my visit.

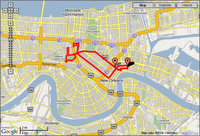

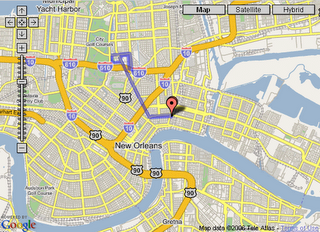

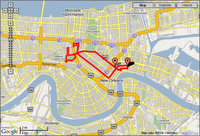

My planned route was simple enough: straight up Canal, left on City Park Blvd., circling the neighborhood by running along the 17th St. Canal up to its upper reach, and then winding through the streets to get a feel of the place. But City Park Blvd. was right-turn only, and every time I tried to make my way back to my original path, it seemed I ran into a new obstacle: the Interstate, a dead end, the railroad tracks. I was riding around singing to myself the old REM tune, "Can't Get There from Here." In the end, I had to double back and be satisfied with seeing only the lower portion of the neighborhood. I'll have to figure out how to get to the upper reaches of "Lakewood" some other time. (Maybe up there they really do call it "Lakewood," after all.)

In addition to the country club and the mammoth Metairie Cemetery (which, as you've probably guessed by now, is

not in Metairie), this neighborhood is home to the

Longvue House and Gardens, creating a near-contiguous expanse of green space not to be trod upon. Which didn't stop the jogger I saw, in biking shorts and polo shirt with collar turned up, iPod buds in place, setting out along the gravel paths of the cemetery. It did leave me with the continual sense of being on the perimeter, but there were some fairly compelling sights even in the borderland.

One of the things that I found most striking along the route was the direct correlation between the size of a house and the likelihood that its occupants were back in it. The great majority of the stately houses lying between Metairie Cemetery and the canal had lights burning in them. On the front lawns of the few unoccupied ones, FEMA trailers were less likely than port-o-johns for the construction workers. The more modest homes, in the area bounded by the curve of the I-10/I-610 split (which might technically be part of "Navarre," another neighborhood no one seems to have heard of), were even-parts occupied, FEMA-trailered, and ghostly. And a fair number of the houses in each category had "for sale" signs out front.

I snapped a photo of a house that seemed to make a definitive statment, "Can't get fooled again." Then there was the neighborhood at the lower edge of the country club. Here, where the smallest houses of the area congregated, I saw fewer FEMA trailers and more remaining debris. It's not that there isn't a general correlation, citywide, between financial status and the chances that you're back (with some major exceptions), it's just that this area provided the handy graphic to go with that data: little green Monopoly house means struggling to get back; big red Monopoly-hotel-sized house means "we're back and love the new kitchen."

By the way, the cemeteries here are "cities of the dead"--to use the goth-club-cum-drama-club tourguide term of choice--just like the more famous

St. Louis Cemeteries. But the vaults and monuments in Metairie and

Greenwood Cemeteries are much grander. I love the great elk stag standing guard at the Elks club tomb at the gates of Greenwood. But, since biking around cemeteries after dark isn't exactly a hobby for me, I decided it was time to find a drink.

In my quixotic circumnavigation of the neighborhood, I had crossed a number of promising local taverns, but none of them appeared to lie within the bounds of the Lakewood neighborhood as defined by my trusty map. Under the shadow of the I-10 at Metairie Rd., however, was the lately reopened Semolina pasta restaurant, a place I had heretofore only seen from the vantage of my car at 60 mph. A sense of duty to my self-appointed task combined with the fact that I had skipped dinner seemed to make this place my next logical stop. Now, in another lifetime, when I was living in Baton Rouge, the Semolina franchise there once seemed the height of culinary hipness, their world pasta serving as the culinary equivalent of "world music." So, on minor special occasions (e.g., payday), we would sometimes indulge ourselves by going beyond our usual burger budget and attempt such exotic delicacies as Pad Thai. Since then, Semolina had somewhat fallen in my estimation and had become for me (unfairly, I must admit) a local would-be Applebees. So, to be honest, I wasn't expecting much from this visit.

My visit began unpromisingly enough with an apology from my bartender (later identified as Lainie, accomplice to a more liquid evening than I had anticipated) for the lack of top-shelf booze behind her bar. The bar seemed to have a dispraportionate number of liquors that generally contribute to the psychedelic hue of the Bourbon St. gutter sludge on spring break weekends, bottles whose labels promised unholy infusions or announced the physical repulsion appropriate to their contents ("Pucker?" Espresso-laced vodkas? (yes, "vodkas," plural)). So, I decided to play nice with a glass of Pinot Noir and a plate of shrimp portofino over linguine (which turned out to be a succulent treat).

If my embarrasing failure to navigate the neighborhood had not been humbling enough, Lainie's contention that I was still a tourist in New Orleans (because I haven't lived here 10 years yet) certainly sufficed to put me in my place (or make me wonder what that place might be). (Although her residency test--ability to find one's way around on the West Bank--did seem a bit arbitrary.) I asked her how the neighborhood fared during the storm: "Well, we had water everywhere. We were living in Venice for three days, I always tell people." Apparently she and her boyfriend, both bartenders in town, had loaded up on ice from their respective bars, stockpiled food in the deep freeze, filled the bathtubs with water, and rode out the storm. Surrounded by water, they grilled out, lit mosquito coils, and waited for the flood waters to subside. "We'd see the police coming by in boats, and they'd call out, 'Y'all need anything?' And we'd say, 'No, thanks. Y'all want something to eat?'" And, according to Lainie, everything was fine until they were forced to evacuate, when they spent two nights sleeping out on the I-10 by the Kenner Galleria, suffering sunburn and dehydration while awaiting a bus that would accept them with Laine's three dogs, one 17 (with two teeth, she says), one 12, and one year-old puppy. Eventually, they were picked up, but they weren't allowed to stop in Baton Rouge (where she has a brother). Instead, they were forced on to Houston, where they had to rent a house until they could get back into the city.

In the middle of her story, a waitress named Gabriella came over to the bar and insisted on watching "America's Next Top Model" on the bar television. She solicited opinions from fellow waitstaff as to whether she should attempt Tyra Banks's latest hairstyle. Lainie wondered aloud whether she should be tending to her tables, but Gabriella insisted, "Hey, I'm doing them a favor." ("Them" apparently meaning the management.) "You're doing them a favor by watching 'Top Model?'" "Girl, I'm doing them a favor by being here. They know I don't work on Wednesdays when my 'Top Model' is on."

Gabriella was slim and sassy with sculpted, high-fashion makeup, but I kept finding myself looking at her hands and wondering if maybe . . . if maybe she was only a part-time female. Lainie quickly cleared that up for me before I could find a way to phrase it: "All my gay friends just love that show. Particularly the ones who do drag." And maybe it was just the effect of the series of lagniappe drinks that somehow found their way in front of me (the first, a glass of red Sangria mistakenly poured for a customer who had ordered white sangria--something none of us at the bar had ever seen), but whatever the reason, I immediately became quite fond of the place. Watching Gabriella go about her shift reminded me that, even at its outer reaches, New Orleans is still New Orleans.

I took Lainie's advice and headed home via Esplanade, rather than Canal. It was one of the handful of temperate nights we get each year, and the city's wild and distinctive odors spread out along the night air, each waiting to ambush my senses. From the fungal, fetid dankness of rotting sheetrock to the seductions of night blooming jasmine, I could mark my progress (and the city's, it seemed) nearly by scent alone. Down by Port of Call, I passed a couple skirting a tiff: he hung back, an "aw-baby" sheepishness in his step and on his face; she strode ahead, knowing he was coming after, knowing he'd

better be coming after. And half a block past them, her perfume caught up with me, stronger than the jasmine, and I thought I felt some hint of her sway.

Down on Frenchmen, every bar had a band worth seeing. I peeked in at Walter Wolfman Washington before checking out my friend Sticky-T's all-girl blues band. When I finally decided to call it a night, the girls were playing "Don't Advertise Your Pain," and I wasn't feeling any.